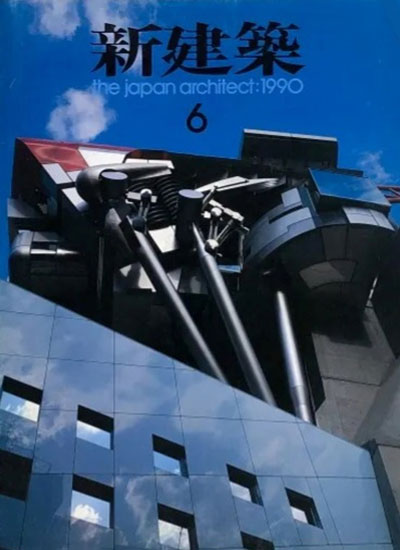

AOYAMA TECHNICAL COLLEGE1990

- 1988

- International Design Competition for AOYAMA TECHNICAL COLLAGE 1st Prize (Japan)

- 1994

- HYLAR International Award (USA)

Self-Organization / The Power of Architecture Restored

Each one of them should grow in its own way,

and yet the overall balance should be achieved.

The winning work in the international design competition

CHALLENGE FOR THE ORGANIC IN URBAN SPACE

Metropolitan Tokyo

The site lies in Shibuya, which is one of the main sub-centers of the downtown area of metropolitan Tokyo.

It is a sprawling, unorganized district filled with a hodge-podge of office buildings and shops, condominium high-rises, and apartments, typical of its kind in Japanese cities. Even Japan, as well known from the example of Kyoto, has its neatly organized cities that have developed through the centuries. But what semblance of order had been carefully fostered during the Edo period (1603-1867) for Tokyo was destroyed by the bombing of Tokyo toward the end of World War II, and in the ensuing rush of rapid economic growth, comprehensive, well-thought-out city planning was ultimately never carried out, leading to the disorderly urban sprawl we observe today .

But for all the apparent disorder and disorganization, it is a city unlike any other in the world: its crime rate is low, traffic accidents are relatively few, its economy is extremely efficient, advanced technology continues to shape and reshape the city, the arts and culture, especially recently, have begun to thrive there, and people of all kinds gather there from all over the country, all in all making it one of the most dynamic and exciting cities in the world today.

Yet in fact, the impression of confusion in the city is undeniable.

Architecture for Tokyo

What does the building of a single piece of architecture mean in a city like Tokyo? What can it do for the city ?

Just one building cannot accomplish much in carrying out a grand urban plan. And yet, it must not be closed to itself and cut off from its surroundings either; otherwise the city would become nothing but a cluster of disconnected, unrelated buildings. Architecture ought to represent the effort to find a way for even one structure to have some effect on the city.

Tokyo is built on different principles from those that govern Western cities. There are no clear boundaries dividing the city from its environs, and few broad, long avenues that afford grand vistas. Zoning regulations are ambiguous, so buildings of all kinds mix and mingle.

One-story dwellings cluster at the feet of skyscrapers. Behind the large commercial firms clustered in major city centers, are labyrinths of alleys filled with factories, drinkeries, dwellings, and shops.

But this city still manages to function smoothly. Why ?

Self-Organization

There is no common standard in Tokyo that defines what a new building should be. There is not so much as a single concept of how individual buildings should be built in order to create the ideal city nor any strict legal regulations to achieve such a goal.

Instead, each building somehow responds to its neighbors and the overall urban milieu, working out a principle of design on its own.

On the surface, these separately conceived buildings look disconnected, but in fact they form real relationships with one another.

The whole takes shape spontaneously, without overall controls or coercive regulations.

The whole creates its own integrated system, through the self-organizing relations that form among its parts.

This urban order is one that comes about of itself; it is not forced by means of strict regulations imposed from above.

It is an order not visibly planned or organized, not based on any one single principle, but dynamic and flexible enough to absorb all manner of changes and still continue functioning.

Tokyo is built according to mechanisms that permit maximum liberty to individual parts and promote their integration into the whole , rather than subjugating them to the whole. They operate on a principle that seeks a free and well-balanced order that does not stifle individuality or undermine the whole.

This organic principle of urban growth is not unique to Japan and Asia. In Western Europe, too, it is thought that cities built on a similar principle existed prior to the Renaissance, although they vanished with the advent of the modern age. It is possible that this principle offers the answers to many of the various problems that plague cities today, not only in Japan but all over the world.

Toward a New Formative Principle of Order

The self-organizing, organic system that emerges on this principle, however, is-like a natural phenomenon-not conscious.

As long as it remains an unconscious principle, it is difficult to draw upon in creating, for example, some building.

By extracting from the spontaneous workings of this principle those methods that we can consciously apply, it is possible that we might develop a conscious principle upon which to create a new architecture for the city.

The Aoyama Technical College aims to discover such a principle for establishing a new order

Message for the City

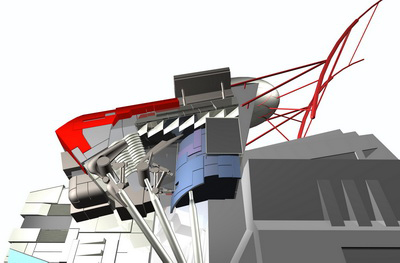

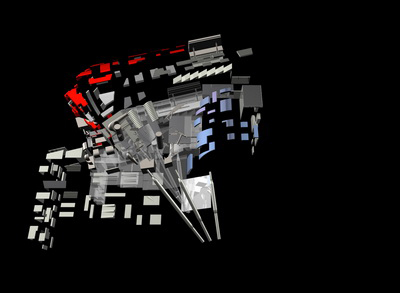

This building consists of many parts.

They all are essential architectural elements-posts, water tanks, lightning rod, joints of various kinds.

But these parts, even after fulfilling their required functions, maintain the momentum of their growth, rising up like so many young shoots flourishing upon a sufficient supply of water and light.

But if they all continued to grow arbitrarily, friction would arise among them, causing the collapse of the whole.

Spontaneously, the growing parts begin adjusting their relationships, considering one another and altering themselves accordingly.

This works to create a harmonious whole through self-organization, in the same way the body of a living thing is made of many different, independently functioning types of tissue.

Here we see an approach in which diverse parts, while pursuing their own vigorous fulfillment, achieve an integrity of the whole without being forced to do so from above. Individual autonomy is respected, a theme that befits a building that houses a college.

It represents a new order, not achieved through simplistic control from above but through tolerance of chaos.

This interaction among parts can be expressed using the Japanese word" ma" (the space or distance among parts).

It offers the possibility for transcending the dichotomous principle of modernism that divides everything into two categories, and refuses to accept anything in between.

The Power of Architecture Restored

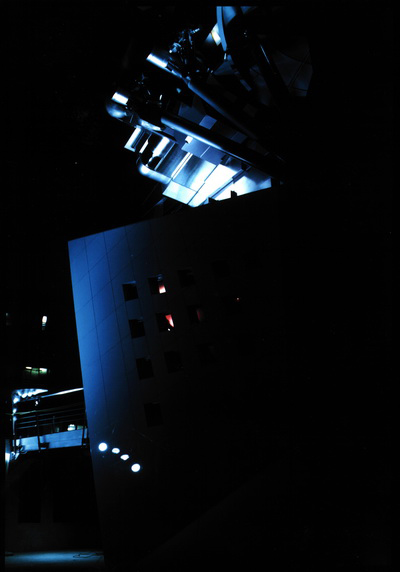

The Aoyama Technical College building is also intended to restore the fundamental strength that buildings ought to have.

Ancient structures, from the Pyramids to the great cathedrals, possessed the awesome power of large spaces.

Most of modern architecture, it seems to me, has lost this basic power. Architecture ought to be something capable of moving people's hearts and giving them a physical thrill in a way possible in no other art.

That power deserves to be restored.

Another purpose of this building is to assure that anyone who might see it experiences, both mentally and physically, an definitive feeling of excitement.

Toward Cities Beyond the Modern Age

The completion of this building proved a potent stimulus to the disorderly, chaotic area in which it stands.

The effect of this structure proposing a new principle for creating architecture in the city will spread, helping people to stop and think about the way they want their cities to be.

They can thus change their communities, as well as Tokyo as a whole, into better worlds.

It is not my aim either to transplant to Japan the classic Western patterns of building cities or to put up with the chaos of Tokyo at it is, but to grope for the way we want the new city to be.

- Movie

Article published in 1990

The following is an article published in a magazine by the author at the time of the architecture’s unveiling in 1990.

Looking back at it now in 2025, the writing style may seem pedantic, but at the time, it reflected the mood of the era as it shifted from the euphoria of the 1980s to the stagnation of the 1990s, and the determination, pride, and a touch of arrogance of a 30s about to set sail into the unknown future.

I hope you can sense a glimpse of that spirit in the text.

This architecture was selected in an international design competition.

The reason for its selection can be summarized in the words "fitness" and "impact."

This was a matter of its suitability as a solution and the expectations for it as a work of architecture.

Here, the intention was to avoid putting an architectural protective layer on the desired space/form.

The constraints that were to be lifted were not merely about shifting the corpus of citations, but about everything from prevailing social attitudes like history and trends to customs and common sense, and even the methods and systems of production and construction, all of which are embedded in each process.

In other words, in the design process, it meant increasing the number of dictionary discs to choose from and slotting in an expanded memory.

In that sense, this is an "expanded architecture," a "distant architecture."

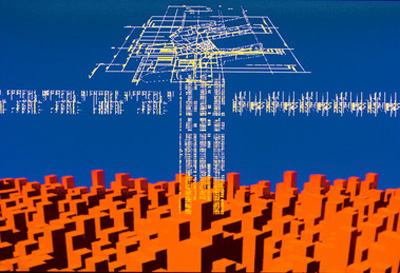

Based on that preparation, the necessary elements were arranged in a 3D virtual space that served as a background world.

Each of these elements, driven by the primary role they were born to fulfill, grows in a certain direction while interacting with the field and other elements.

By generating and drawing out this directional energy, they achieve a plant-like growth even after they have fulfilled their given duties.

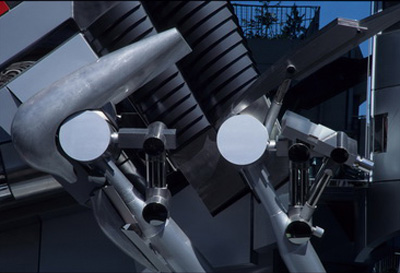

The gallery on the top floor becomes a multifaceted solid that juts out into the sky, and at the point where it connects with the supporting pillars, complex "harts" sprout.

The lightning rod extends, the windows stop being openings and become lumps, and colors shower down on all of them.

If the collision of these self-governing parts is presented as a cross-section of a phenomenon, a discrete urban model of reality is transcribed onto it and emerges.

However, here, while promoting the honest autonomy of the elements, a further integration of the whole was sought.

The intention was to establish a "reintegration" relationship of a different dimension from the past in a structure that was once scattered.

The code adopted for this was multi-layered.

This act would result in the weaving of "anti-anti-romance" within a gentle system of movement, transition, sensuality, and possession.

Furthermore, in order to measure the distance of effects by such processing, established standard clichés were used as positioning indicators.

The accelerated solid of the entrance hall, made of crystallized glass, is an example of this.

And in the materialization of all of these, the construction of a diverse, small-batch production system using CAD/CAM, which had not yet appeared in architecture, and the "hyperquality-ization" of details were demanded.

Eventually, this architecture took off from the smoke of a harsh battle, with a de facto design period of 3.5 months and a construction period of 10 months.

Translation in current language

Following is a 'Translation in current language’ of the original text. (Green text / a free translation)

This architecture was selected in an international design competition.

The reason for its selection can be summarized in the words "fitness" and "impact."

This was a matter of its suitability as a solution and the expectations for it as a work of architecture.

This architecture was selected in an international design competition in 1998.

The reason for its selection was, first, it was recognized as an excellent solution to the subject, such as proposing a free space on the top floor not included in the competition requirements, despite the narrow and difficult site.

Another reason was that it was expected to have the power to create new value in the field of architecture.

Here, the intention was to avoid putting an architectural protective layer on the desired space/form.

The constraints that were to be lifted were not merely about shifting the corpus of citations, but about everything from prevailing social attitudes like history and trends to customs and common sense, and even the methods and systems of production and construction, all of which are embedded in each process.

In other words, in the design process, it meant increasing the number of dictionary discs to choose from and slotting in an expanded memory.

In that sense, this is an "expanded architecture," a "distant architecture."

Usually, architects impose invisible rules on themselves.

These rules include ideals and norms about what good architecture should be, as well as customs such as “this is how we always do it.”

One such rule is “form follows function.”

Here, I started the design process with the mindset of not only setting aside such design philosophies but also the methods of component production in factories and construction site work, in order to find a method that better suits the purpose.

From this perspective, this could be described as an architecture that is “far removed” from previous architectural practices.

Based on that preparation, the necessary elements were arranged in a 3D virtual space that served as a background world.

Each of these elements, driven by the primary role they were born to fulfill, grows in a certain direction while interacting with the field and other elements.

By generating and drawing out this directional energy, they achieve a plant-like growth even after they have fulfilled their given duties.

The gallery on the top floor becomes a multifaceted solid that juts out into the sky, and at the point where it connects with the supporting pillars, complex "harts" sprout.

The lightning rod extends, the windows stop being openings and become lumps, and colors shower down on all of them.

Based on these policies and preparations, I placed each element of the architecture within the three-dimensional space envisioned during the design phase.

These elements include component units like rooms, walls, and windows; structural elements like columns and beams; and equipment like elevated water tanks and lightning rods, and other parts that make up the building.

While they are diverse, but in normal design, it is sufficient for them to fulfill their intended functions.

However, in this case, I considered each part as if it were a growing organism.

Living things do not simply fulfill their purpose and then cease to exist; rather, sometimes they continue to grow as long as conditions permit.

If left unpruned, even a weak street tree will grow tall and become a large one, or even a small goldfish in an aquarium will grow to enormous sizes if released into a river.

Similarly, rather than suppressing the “momentum of growth” of each part of the building, I attempted to extend it further.

This is also related to the fact that this architecture is a school.

For students, it is not enough to simply complete their assignments.

They are expected to have an attitude of wanting to go further.

The lightning rods extend even further upward, the windows become blocks of light, and magical shapes appear where the columns and beams meet.

Above all this, the (imaginary) light that pours down overlays patterns of color.

If the collision of these self-governing parts is presented as a cross-section of a phenomenon, a discrete urban model of reality is transcribed onto it and emerges.

If we consider this to be complete, it may result in a so-called chaotic state, similar to the streetscape of Shibuya surrounding the site, where each building asserts itself each other without much regulation.

However, here, while promoting the honest autonomy of the elements, a further integration of the whole was sought.

The intention was to establish a "reintegration" relationship of a different dimension from the past in a structure that was once scattered.

However, this design does not seek chaos, but rather recognizes the freedom of each individual while simultaneously striving to achieve overall integration.

This is a task that is easy to say but difficult to accomplish.

The code adopted for this was multi-layered.

This act would result in the weaving of "anti-anti-romance" within a gentle system of movement, transition, sensuality, and possession.

The method used here is not just one, but a combination of several ways.

In short, rather than viewing architecture as simply a “white box,” the aim is to make it something that inspires various associations and imaginations.

In other words, it is okay to think that architecture is cool, to feel its powerful momentum, or to be impacted by it in a way that resonates with your body.

The idea is to create architecture that allows viewers and users to create their own stories based on their impressions and memories of the building.

Through each viewer's story, it is possible to perceive the whole, which seems to grow chaotically on its own, as a single entity.

That was my thought.

Furthermore, in order to measure the distance of effects by such processing, established standard clichés were used as positioning indicators.

The accelerated solid of the entrance hall, made of crystallized glass, is an example of this.

For comparison with these methods, I have placed an example using a well-known design technique.

It is the accelerated cube made of crystallized glass at the entrance.

This technique of “emphasizing perspective” has been well known since the Renaissance.

By experiencing the difference between this type of traditional design, it is assumed that visitors will notice the “new approach” to design here.

And in the materialization of all of these, the construction of a diverse, small-batch production system using CAD/CAM, which had not yet appeared in architecture, and the "hyperquality-ization" of details were demanded.

As mentioned earlier, this “expansion of methods” is not limited to design.

The production of exterior panels, none of which are identical, is similar to the production methods used in the automotive industry, which goes beyond the field of architecture.

A dedicated computer program has been developed by the manufacturing company for the three-dimensional bending of these panels.

Eventually, this architecture took off from the smoke of a harsh battle, with a de facto design period of 3.5 months and a construction period of 10 months.

In terms of exceeding conventional boundaries, the short design and construction periods were also similar.

After overcoming these difficult conditions, this architecture finally appeared on the ground.

Architecture generally stands stable on the land.

However, this architecture seems to be about to start operating and move forward.

This is the beginning of the “story” of each person who experiences this architecture.